This Spotlight features research on coaching and mentoring STEM educators. Three projects share their approaches to supporting mathematics educators through a combination of professional learning, ongoing support, innovative tools, and relationship-building. They share advice on how other DRK-12 projects might approach coaching and mentoring in their own projects and proposals, and discuss the challenges and affordances of mentoring and coaching models.

This Spotlight features research on coaching and mentoring STEM educators. Three projects share their approaches to supporting mathematics educators through a combination of professional learning, ongoing support, innovative tools, and relationship-building. They share advice on how other DRK-12 projects might approach coaching and mentoring in their own projects and proposals, and discuss the challenges and affordances of mentoring and coaching models.

- Featured Projects

- Building Sustainable Networked Instructional Leadership in Elementary Mathematics Through a University Partnership with a Large Urban District (PI: Caroline Ebby)

- Strengthening Middle School Mathematical Argumentation through Teacher Coaching: Bridging from Professional Development to Classroom Practice (PI: Teresa Lara-Meloy)

- Supporting Teachers to Develop Equitable Mathematics Instruction Through Rubric-Based Coaching (PIs: Erica Litke, Jonee Wilson, Heather Hill)

- Additional Projects

- Related Resources

Featured Projects

Building Sustainable Networked Instructional Leadership in Elementary Mathematics through a University Partnership with a Large Urban District

PI: Caroline Ebby

STEM Discipline: Mathematics

Target Audience: K-8 Teachers

Project Description: Through a research-practice partnership between the University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education and 14 under-resourced neighborhood elementary schools in the School District of Philadelphia, the Responsive Math Teaching project has been developing and refining a model for mentorship of instructional leadership that focuses on:

- Developing a shared understanding of high-quality inclusive math instruction

- Ongoing professional development

- Support For Classroom Implementation

- Leadership mentoring and development for sustainability

- Ongoing research for continual improvement

RMT builds instructional leadership through three phases. Teachers Experience responsive math instruction as learners and reflect on that experience in relation to facilitation practices. Teachers learn about, try out, and Teach with new instructional practices while engaging in grade-level cross-school Collaborative Lesson Design groups. A select group of teachers and leaders move on to Lead sessions, learning to plan and facilitate professional development for the other cohorts.

RMT provides a much needed on-ramp for professional growth and leadership. Members of the project team mentor school-based instructional leaders to increase their capacity to provide support to math teachers in responsive teaching practices. Teacher leaders learn to lead professional development, reducing the need for university-based support, and ensuring sustainability.

What challenges have you experienced related to mentoring/coaching work and what strategies have you identified to address them?

We realized early on that given the high rate of teacher turnover in this large urban district, we would need to develop instructional leadership capacity in a cadre of potential teacher leaders at each school. In addition to the designated math teacher leader, we worked with schools to identify and recruit additional grade level teachers to receive mentorship in preparation for acting as leaders in our project and in their own schools. This ended up as a mutually beneficial endeavor, as a number of these classroom teacher leaders were later chosen for instructional leadership roles in their schools as those positions opened up. We also utilized mainly classroom teachers to lead cross-school, grade-level lesson planning and debrief groups, as their expertise proved to be a good fit in that role.

What impacts or benefits are you seeing related to mentoring or coaching?

When our project began, our professional developments for educators were run by members of our small project team. Mentoring school-based teachers and leaders into leadership and supporting them to learn to run our PDs was always a goal of this project, because we wanted the work to be sustainable and for the expertise we developed to live within the schools. Mentoring new leaders also affected the scale and scope of our project as we invited new teachers and schools each year. Additional leaders meant that more PDs at a greater variety of days and times could occur, which broadened the size of the professional learning community we were building. Additionally, inviting people into leadership in our project added new ideas. We found that our novice leaders modified and adapted our programs to fit their own styles, to meet the needs of their participants, and to make them work even better for the school community while maintaining the integrity and focus of the work we are doing, which has been an unexpected but exciting benefit.

What factors do you think most contribute to successful relationships between mentors, coaches, and those whose knowledge and skills they aim to improve?

Realizing how much of this work is relational is extremely important. We run our various professional development groups as communities of practice, allowing leaders who are being mentored to apprentice into the role, modeling responsive leadership and adjusting the level of support we give them as needed over time. We support them as they work to develop spaces where people feel safe to be vulnerable and to share developing ideas, always focusing on creating a culture of working together towards improvement. Our mentorship follows a predictable pattern: first we plan together, then enact the professional development, then debrief the experience. This format allows us to continuously set goals, assess our progress on those goals, and then refine them for the next time.

Initial findings: Our ongoing analysis of data collected over 5 years of teacher leadership development provides insight into both common patterns and variability in the growth of leadership that is responsive to teacher learning, adding important dimensions to existing conceptualizations of the knowledge and skills that are involved in developing elementary math instructional leadership.

We constructed case studies of 6 instructional leaders over 5 years of participation in the project. Cross-cutting themes in their leadership development include developing a teacher leader identity, cultivating trust and community, and learning to support teachers as learners. Novice leaders developed confidence in themselves as leaders and learned to value their own experience and expertise. They also learned to build rapport with teacher learners by helping them feel comfortable sharing artifacts of practice and highlighting how much learning resulted from sharing, providing feedback, and reflecting on practice. Finally, while leaders often struggled to be more intentional about supporting other teachers as learners, over time they learned to draw out teacher participant ideas, press for pedagogical reasoning, and connect to general principles of teaching and learning, student understanding, and/or future instruction.

Our analysis of collaborative discussions around video artifacts of teaching resulted in a framework for focused responsiveness, where teachers are positioned as having expertise and agency, and knowledge is co-constructed by the group. Structuring moves ensure that the group members understand and stick to the goals of the session. Eliciting moves allow the facilitator to create space for participants to make the important points in a discussion, share ideas, and make connections. Cultivating moves function to build the community of the group, and connecting moves are critical for supporting pedagogically productive discussions. As teacher leaders took over more facilitation responsibility, they increased their use of structuring and cultivating moves; some also increased in either connecting or eliciting moves. Moreover, these increases were often concurrent with decreases of those moves by the mentors. This suggests that the mentor was modeling facilitation moves in the beginning of the year that were then taken up by teacher leaders in later sessions. (Ebby et al., 2023)

Product(s):

- Project Website: https://www.gse.upenn.edu/academics/research/responsive-math-teaching

- Video: Developing Responsive Math Teaching and Leadership. 2021 STEM for All Video Showcase, May, 2021.

- Educator Facing Products:

- Responsive Math Teaching Instructional Model https://repository.upenn.edu/handle/20.500.14332/35340

- Responsive Math Teaching: Planning and Coaching Protocol https://repository.upenn.edu/handle/20.500.14332/35339

- Research Reports:

- Ebby, C.B., Hess, B.R., & Pecora, L. (2022, April). Developing Teachers’ Instructional Vision for Inclusive Math Practice: The Role of Epistemic Experience. Paper presentation at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San Diego, CA. https://repository.upenn.edu/handle/20.500.14332/8243

- Responsive Math Teaching Project (2021) A Model for Developing Sustainable Math Instructional Leadership. CPRE Working Papers. https://repository.upenn.edu/handle/20.500.14332/8472

- Ebby, C.B., Hess, Pecora, L., & Valerio, J. (2021). Teaching Them How to Fish: Learning to Learn and Teach Responsively. CPRE Working Papers. https://repository.upenn.edu/gse_pubs/558

- Ebby, C.B., Hess, B.R., Valerio, J. & Pecora, L. (2023, April). Facilitating collaborative discussions around video artifacts of mathematics teaching. Paper presentation at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Chicago. https://repository.upenn.edu/handle/20.500.14332/59365

- Valerio, J. (2023). Investigating synergies and take up when practice-based professional development and collaborative lesson design are used in tandem [Doctoral Dissertation] University of Pennsylvania.

- Ebby, C.B., Hess, B., Valerio, J., Pecora, L., Goldsmith-Markey, L., and Davis, J. A. (In Press). Developing Equitable Teaching Practices Through Facilitated Teacher Learning Communities. In C. Koestler & E. Thanheiser (Eds). Building Community to Center Equity and Justice in Mathematics Teacher Education, AMTE Professional Book Series Vol 6. Association of Mathematics Teacher Educators.

Strengthening Middle School Mathematical Argumentation through Teacher Coaching: Bridging from Professional Development to Classroom Practice

PI: Teresa Lara-Meloy

STEM Discipline: Mathematics

Target Audience: Middle school math teachers and their coaches. However, because we aim to work with school teams as much as possible, we have some 5th grade teachers in the mix.

Project Description: For each and every student to experience math classrooms in which they can thrive, new classroom practices are needed. Visualize Teaching (at TERC), is based on over two decades of research into supporting teachers towards this goal. This research and design program is focused on mathematical argumentation, the social practice of understanding mathematical truths together. It's the key work of mathematicians, and each and every student should engage in this rigorous disciplinary practice. Building on the productive coach-teacher relationship, Visualize Teaching supports teachers as they expose the mathematical underpinnings of school mathematics.

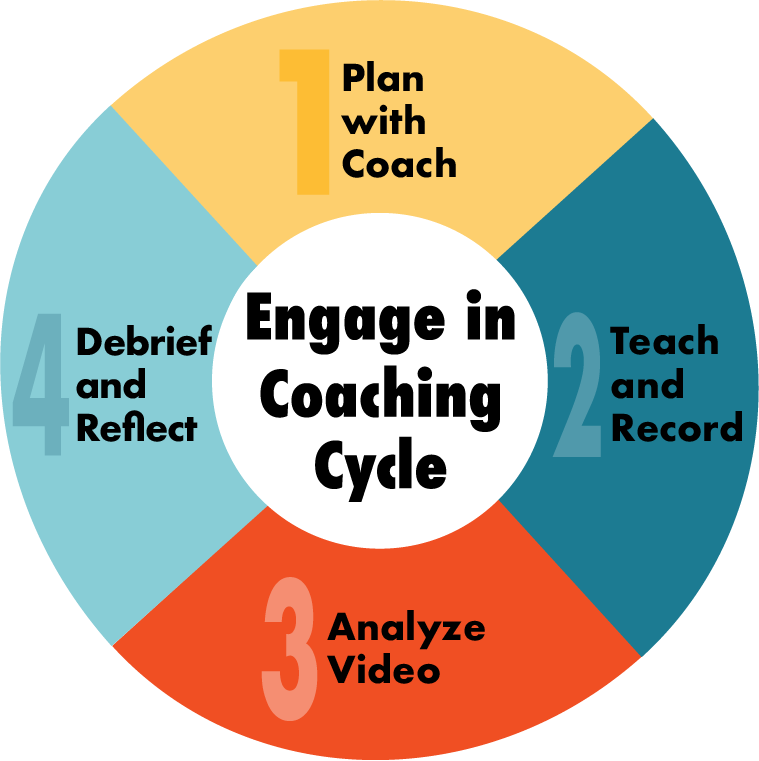

Visualize Teaching is a 2-year professional learning program where coaches and teachers learn mathematical argumentation together during week-long summer workshops. During the school year the coach-teacher dyads engage in cycles comprised of four phases: a coach-supported teacher visualization of a math argumentation-focused classroom lesson; a teacher leading the visualized lesson that they self-videorecord; a time to review the lesson and the videorecording for the teacher and the coach independently; and finally, a coach-teacher debrief of the lesson. Meanwhile, the group of coaches meet monthly with the professional development team to discuss coaching issues as they emerge. Coaches share concerns, questions, and best practices with one another.

The research is funded as a design and development DR-K12 project on teacher learning. Our research questions focus on understanding the impact of the professional development on the teacher and students classroom practices: how are the teachers supporting students in engaging in mathematical argumentation and what is the quality of students classroom mathematical argumentation.

What advice would you give to other projects that are considering incorporating a mentoring or coaching component into their approach? We proposed the inclusion of mathematical coaches, both as a natural progression of our research in professional development and because it is one of the best practices in effective in-service professional learning. There are many benefits to including coaches per said research. And our initial findings bear this out. We can see direct lines between the sessions where the teachers visualize the math argumentation with their coaches with what is seen in the classroom videos and in their debrief sessions.

We found that the coaches helped immensely with data collection in a way that we had not entirely anticipated. Because we met regularly with the coaches (but not the teachers) during the academic year, we learned about changes happening at our schools, and we relied on their existing relationships to encourage the teachers to schedule and complete the coaching cycles. We recommend including sufficient funds to allow for this type of support.

The biggest thing to consider when including coaches or mentors in a project is around recruitment. Our recruitment was more complex than we had anticipated, because we wanted teams of middle school math teachers to come with their own middle school math coaches. So, both teachers and coaches had to agree to participate in our two-year study, which included two week-long summer workshops and ongoing data collection during the academic years. We recommend including enough funding and time to account for this participation complexity.

What challenges have you experienced related to mentoring/coaching work and what strategies have you identified to address them? We work with existing teams of coaches and teachers. Because we started this project during the year of online teaching, we recruited as broadly as possible, not just in the districts where TERC staff were located. We spent additional money and time towards this effort. We worked with existing contacts, asked our board and other TERC researchers to help, sent out hundreds and hundreds of emails, ran an extended social media campaign, and tried recruiting coaches and teachers by posting on sites like NCTM and NCSM. There were several times when we had invested several months in building a relationship with district folks and principals, had met with school coaches, when suddenly, then the district or principal priorities or funding changed.

Attrition is another challenging area. During the last few years, we have had solid district partners with unwavering commitment to the professional learning of their math teachers through coaching. However, some of our coaches have left our participating schools or changed roles. When one coach left her school in the middle of the first school year, their new coach was not a math specific coach and did not feel comfortable joining a project midway. We had to be flexible and provided a non-school based math coach to prevent our teachers there from also having to leave the project. This new coach was not an existing employee of the school district, so our project had to make room in our budget to pay for their services.

What impacts or benefits are you seeing related to mentoring or coaching? We have video recordings for three of the stages of the coaching cycle (see right image): the visualization planning of the argumentation lesson, the teaching of the lesson itself, and the reflection after each person has looked at the data. The cycles provide opportunities to narrowly focus on one particular math practice: argumentation. We see coaches helping the teachers unpack the mathematics in the lessons, listen and annotate the lesson when teachers are visualizing their teaching moves, and help focus the debrief conversation on the consequences of those teaching moves (students’ actions, behaviors and learning). The coach and teacher both see the specific questions and teaching moves that they planned show up in the classroom videos. This personal, individualized focus on a teachers’ craft is meaningful to the teachers and the coaches, especially as they have tangible evidence (in video form) of those plans.

One teacher in her second coaching cycle realized how little talking her students had been doing. In her third cycle, she visualized ‘sitting down’ during the whole class discussion and ‘letting the students lead the class.’ Both the coach and teacher were thrilled to see the results of this action in the classroom video and spent a long time discussing how this move helped students ask more questions of each other, without her as the constant intermediary or referee.

What factors do you think most contribute to successful relationships between mentors, coaches, and those whose knowledge and skills they aim to improve? One of the key aspects of our project is that both teacher and coach are learning about mathematical argumentation together. This joint learner positionality creates a degree of camaraderie and is crucial to working together in the lesson visualization and post-lesson analysis and debrief.

Our most successful coaches also approach their coaching conversations with gratitude, curiosity and wonder. Our teachers sometimes feel, understandably, vulnerable when opening their classrooms, especially when sharing video of their classrooms. We see coaching conversations go smoothly when the coach acknowledges the gift the teacher is offering and they show curiosity about what is happening in the classroom, instead of judgement.

Finally, but not lastly, the individualized attention is a huge factor in successful coaching relationships. For each lesson, the teacher gets about 90-180 minutes of individual time with their coach to visualize particularly difficult parts of a lesson, try out new teaching practices, and reflect on what happened.

What supports are you developing and/or providing your mentors/coaches? (why?) We provided three types of support for our coaches.

First, we developed a wrap-around coach-only workshop beyond the one-week mathematical argumentation workshop that was attended by teachers and coaches as they learned together. This additional time together in the coaches’ first year helped the coaches learn their responsibilities in the research project and helped them see how Visualize Teaching fit within their own coaching goals and practices.

Second, we provided agendas and a discussion guide for each of the four stages of the coaching cycle, especially as it pertained to math argumentation and its teaching practices.

Third, we met with the group of coaches monthly for an hour and a half to discuss issues of coaching practice, which included how to schedule sessions with reluctant teachers, how to help teachers visualize their lessons, how to focus the debrief conversations, and how to give feedback without being evaluative. Sometimes, we watched videos from the coaches’ sessions with their teachers to ground the conversation on their own practice.

Initial findings: We are currently working on writing reports and papers.

Product(s):

- Video about Visualize Teaching produced for NCTM TV 2023

- Website: https://www.terc.edu/viste/

Supporting Teachers to Develop Equitable Mathematics Instruction Through Rubric-Based Coaching

PIs: Erica Litke, Jonee Wilson, and Heather Hill

STEM Disciplines: Mathematics

Target Audience: Mathematics instructional coaches and upper elementary and middle grades mathematics teachers

Project Description: HEAR-MI Coaching, a mathematics instructional coaching model, aims to improve middle grades mathematics instruction by providing a framework for and support to mathematics coaches working with teachers to develop more equitable instructional practices. HEAR-MI Coaching leverages a video-based coaching model and a set of coaching routines alongside a set of equity-focused, mathematics-specific classroom observation rubrics (Equity and Access Rubrics for Mathematics Instruction [EAR-MI]). Coaches and teachers analyze instruction through the lens of the EAR-MI, a set of rubrics attending to research-based instructional practices that support historically marginalized students’ mathematics success. Participating coaches and teachers work together through coaching cycles. They first set goals related to an EAR-MI rubric. Next, they engage in routines in which they use the EAR-MI rubrics as a lens for reflecting on and analyzing video clips of mathematics instruction, both from the project library as well as the teacher’s own classroom. Through these routines, coaches guide teachers to identify concrete ways they might elevate their instruction in relation to their goals and the focal EAR-MI practices. Teachers then identify a specific goal for the next coaching cycle, with HEAR-MI coaches acting as facilitators or guides for the teachers as they work toward their self-identified goals. Through this project, we seek to understand how and in what ways HEAR-MI Coaching supports teachers to develop more equitable instructional practices, supports teachers’ beliefs about and self-efficacy for doing so, and how the model impacts students’ identity development, achievement, and participation.

What advice would you give to other projects that are considering incorporating a mentoring or coaching component into their approach?

Coaching is difficult and relational work and there are many documented obstacles to coaches successfully partnering with teachers around instructional improvement. Furthermore, coaches face competing priorities and can easily be pulled away from coaching activities. We have found it critical to have a committed district-level partner who is enthusiastic about the proposed coaching work, who prioritizes the time and resources needed for coaches to successfully work with teachers, and who reduces barriers to coaches enacting project activities with teachers. We also suggest that projects aim to reduce the costs of participation to teachers and coaches. For example, if video recording of classrooms is a part of the project, consider hiring someone embedded in the district or on site to coordinate scheduling and recording. This reduces logistical burdens on coaches and teachers and allows them to focus on coaching.

What challenges have you experienced related to mentoring/coaching work and what strategies have you identified to address them?

A major challenge for coaches and teachers in our project has been limited time and competing demands. For example, coaches and teachers are not always able to dedicate sufficient time to complete full coaching conversations given the multiple constraints faced in their daily work. In addition, the nature of coaching work is somewhat flexible and, as a result, coaches are frequently pulled away from coaching to other responsibilities unrelated to coaching. To accommodate these challenges, we have adapted our model so that it can be used flexibly. For example, different components of a coaching conversation can be held in separate, shorter meetings (e.g., at one meeting, the coach and teacher discuss stock video; at the next meeting, they discuss the teacher's own video and set goals). Coaches also have flexibility in how they structure their conversations within the context of the model—for example, working one-on-one with teachers or with several teachers at once in small PLC groups.

What factors do you think most contribute to successful relationships between mentors, coaches, and those whose knowledge and skills they aim to improve?

We have found it important for the coaching work to be teacher-driven. For example, in our project, teachers set improvement goals and determine action steps. They do so in conversation with their coach and grounded in a particular framework, but teachers direct their learning in that context. Another key factor for successful relationships is to establish trust. This work looks different across contexts. Considerations such as where the coach is positioned (e.g., school-based vs. district-based), coaches’ experience in their role (e.g., new to coaching, new to a specific school building), the number of teachers a coach supports, and who coaches support (e.g., new vs. experienced teachers) play an important role in relationship-building and how coaches and teachers establish mutual trust. Another factor that supports a successful relationship is providing structure for coaching. In addition to designated time for coaching, coaches and teachers in our project report benefitting from specific structure and routines that guide their conversations. Finally, we note that coaches are seldom provided with job-embedded training or professional support around coaching work. Providing professional learning for coaches can support those engaging in the work to build effective practices and navigate dilemmas that arise.

What supports are you developing and/or providing your mentors/coaches? (why?)

We provide professional learning for coaches both up front and throughout the school year. Coaches attend a four-day summer training in which they learn the HEAR-MI Coaching model and the EAR-MI rubrics. They watch and analyze video clips of instruction, deepening their understanding of the EAR-MI rubrics and calibrating with one another. They analyze excerpts of coaching conversations as a way to decompose and learn coaching routines. They role-play coaching routines and conversations with project staff and one another as a way to rehearse their coaching with support and feedback. Throughout the school year, coaches attend monthly webinars with project staff in which we collaboratively problem solve around common challenges and debrief classroom video conversations and coaching excerpts. Coaches and teachers record their coaching conversations and project staff provide ongoing individualized support and feedback to coaches as needed. These activities allow for coaches to extend their learning by examining a representation of their practice along with project staff, paralleling the kinds of work coaches engage in with their teachers.

Initial findings: Participating teachers from the pilot year of our project reported that they found HEAR-MI Coaching valuable. In particular, they reported that they appreciated the video component and opportunities to reflect on their instruction in a one-on-one setting with their coach. Additionally, they valued the intentionality of these conversations, noting that the EAR-MI rubrics provided a specific framework for reflection with coaches. Pilot year coaches identified specific ways the project supported them in their work with teachers. They highlighted the importance of ongoing support through webinars and collaboration with other project coaches and project staff. In addition, they named support from their supervisors (who had also bought into HEAR-MI Coaching) as impactful for their ability to successfully implement the coaching model.

Product(s)

Presentations

- Litke, E., Wilson, J., & Akridge, S. Contextual Supports and Obstacles for Enacting Equity-Focused Mathematics Coaching. Poster accepted for American Educational Research Association, Philadelphia, PA. April 2024

- Litke, E., Wilson, J., Akridge, S., & Booth, S. An Instructional Coaching Model to Support Shifting Toward More Equitable Mathematics Instruction. Association of Mathematics Teacher Educators, Orlando, FL. February 2024

- Litke, E., Wilson, J., Akridge, S.; & Sawyer, J., Coaches and Teachers Navigating Tensions and Resonances in Shifting Toward More Equitable Mathematics Teaching. Association of Mathematics Teacher Educators, New Orleans, LA. February 2023

Additional Projects

We invite you to explore a sample of the other recently awarded and active work that focuses on coaching and mentoring in the DRK-12 portfolio.

Coaching & Mentoring STEM Educators:

- Advancing Mentor Teachers' Practices Through Collaborative Pedagogical Reasoning (Collaborative Research: Ghousseini, Remillard, and Shaughnessy)

- CAREER: Equity Focused Elementary Mathematics: Creating Virtual Mathematics Communities in Rural Georgia

- Development and Validation of a Mobile, Web-based Coaching Tool to Improve Pre-K Classroom Practices to Enhance Learning

- Doing the Math with Paraeducators: Enhancing and Expanding and Sustaining a Professional Development Model in PreK to Grade 3 Math Classrooms

- Preparing Mentors to Support Novices in Eliciting Student Thinking during Mathematics Discussions: Developing and Testing a Simulation-based PD Program

- Project AIM-NEXT: All Included in Mathematics New Extensions - Professional Development for K-2 Mathematics Teachers, Leaders, and Coaches (Collaborative Research: Heck and Sztajn)

- Synchronous Online Video-Based Development for Rural Mathematics Coaches (Collaborative Research: Amador and Choppin)

- Testing the Efficacy of the Strategic Observation and Reflection (SOAR) for Math Professional Learning Program

Mentoring K-12 Students:

- Culturally Responsive Engineering Experience Design and Development through Teacher-Undergraduate Engineering Student Partnerships

- Fostering Computational Thinking through Neural Engineering Activities in High School Biology Classes

- Incorporating Professional Science Writing into High School STEM Research Projects

- PBS NewsHour Student Reporting Labs StoryMaker: STEM-Integrated Student Journalism

Mentoring Post-Secondary Students and Early Career Scholars

- CAREER: From Research to Meta-Research to Practice – The Development of an Educational Learning Environment Framework for School Algebra

- CAREER: Promoting Science Motivation and Learning through Instructional Support of Curiosity

- Mentoring a Diverse Cohort of Postdoctoral Scholars in Data Science Education Research

- Workshop for Writing Grants for Early Career Scholars in STEM and Learning Sciences Focused on Racial Equity

Related Resources

CADRE Resources:

Mentoring Post Secondary Scholars

Mentoring Post Secondary Scholars

Read about key elements of effective mentoring for postdoctoral and early career researchers. Find mentoring tips and strategies, as well as example mentoring plans.

DRK-12 Publications on Coaching & Mentoring:

- Bridging the Distance: One-on-One Video Coaching Supports Rural Teacher

This article describes online video coaching model used with middle-grades, rural mathematics teachers… - CHALK Coaching Website

The CHALK tool is a progressive web application that guides educators to improve instructional quality in early education settings. CHALK provides targeted observation… - Coaching from a Distance: Exploring Video-based Online Coaching

This study explored an innovative coaching model termed video-based online video coaching. The innovation builds from… - Examining the sustainability of teacher learning following a year-long science professional development programme for inservice primary school teachers

This two-year, mixed-methods study… - Examining the Use of Video Annotations in Debriefing Conversations during Video-Assisted Coaching Cycles

This study examined how mathematics coaches leverage written annotations to support… - How can coaching knowledge be measured?

How can coaching knowledge be measured? - Making Sense of Sensemaking: Understanding How K–12 Teachers and Coaches React to Visual Analytics

With the spread of learning analytics (LA) dashboards in K-12 schools, educators are… - Mentoring the Mentors: Hybridizing Professional Development to Support Cooperating Teachers’ Mentoring Practice in Science

This article describes key features of a hybrid professional… - Practice What You Teach: A Video-Based Practicum Model of Professional Development for Elementary Science Teachers

This study examines an innovative professional development program that… - Responsive Math Teaching (RMT) Planning and Coaching Protocol

The Responsive Math Teaching Project's (RMT) Planning and Coaching Protocol is an 18-page booklet that includes the RMT… - Supporting Mentor Teachers in the Assessment of and Inquiry into High-Leverage Science Teaching Practices

While the scholarship examining the teaching of high leverage teaching practices in… - Synchronous Online Model for Mathematics Teachers' Professional Development

In this chapter, the authors present the design rationale for and empirical results from a predominantly… - The Impacts of a Research-Based Model for Mentoring Elementary Preservice Teachers in Science

This article focuses on the impacts of a program designed to prepare elementary classroom teachers… - The Missing Ingredient in Science Teacher Preparation: The Role of the Senior Specialist

The traditional model for supervision of pre-service science teachers during the field experience… - Towards an Empirically Grounded Theory of Action for Improving the Quality of Mathematics Teaching at Scale

Our purpose in this article is to propose a comprehensive, empirically grounded… - Variations in coaching knowledge and practice that explain elementary and middle school mathematics teacher change

This study investigated relationships between changes in certain types of…

Related Spotlights: