The DRK-12 portfolio includes a number of projects endeavoring to scale innovations and enact reforms on a systemic level. In this spotlight, explore the types of partnerships, methodologies, theoretical frameworks, challenges and strategies that support this kind of work. This Spotlight includes a perspective piece by Suzanne Donovan and Alan Schoenfeld, highlights the work of seven projects, and offers additional resources for those interested in learning more.

In this Spotlight...

- Community Voice by Suzanne Donovan and Alan Schoenfeld

- Featured DRK-12 Projects

- MIST (Middle-School Mathematics and the Institutional Context of Teaching)

- A Research-Practice Partnership to Develop Math Professional Development Leaders and Build District Capacity

- The Responsive Math Teaching Project: Developing Instructional Leadership in a Network of Elementary Schools

- Science Communities of Practice Partnership (SCOPP): Generating Reform Ownership for Transforming Science Teaching

- Testing a Leadership Development Model for High School Science Reform and the Relationship of Key Variables to Student Achievement

- A Three-Way Partnership to Build School District Leadership in Scientific Argumentation

- TRUmath and Lesson Study: Supporting Fundamental and Sustainable Improvement in High School Mathematics Teaching

Key Features of Successful Partnerships: Reflections from the TRU-Lesson Study Team

Suzanne Donovan, Executive Director, SERP Institute

Alan Schoenfeld, Elizabeth and Edward Conner Professor of Education and Affiliated Professor of Mathematics, University of California at Berkeley

CADRE invited the PIs of the TRUmath and Lesson Study: Supporting Fundamental and Sustainable Improvement in High School Mathematics Teaching project (Grant Nos. 1503342, 1503454) to reflect on the lessons they've learned from their work at the district level.

CADRE: What have you found to be key features of successful partnerships between research and development institutions and school districts?

There are four features of partnerships that we consider of greatest importance to their success.

There are four features of partnerships that we consider of greatest importance to their success.

1. Work on a problem of practice the district cares about/requests help with, and provide the kinds of research expertise and support that aim at solutions to the real problems.

To understand the real problems, it is essential to listen with the ears of someone who is humbled by the complexity of education practice, and has respect for the many types of expertise necessary to improve it. We note that this approach can offer significant challenges and rewards to researchers. On the one hand, standard research methods are unlikely to apply meaningfully to practice without major modifications. On the other hand, researchers are often challenged to develop new methods that expand the capacity of researchers to do work that is meaningful in practice.

2. Provide active support rather than giving direction about what to do.

2. Provide active support rather than giving direction about what to do.

In one interview after another, school and district administrators expressed appreciation for the people who showed up to carry the burden of the work initially, and to support the development of local capacity over time. Without that support (and sometimes even with it), an initiative will be one more demand on time that is already stretched too thin. Often, in order to support ongoing work, designing tools for practice will be essential. The partnership will have a greater chance of success if it includes expertise in design. Here too, researchers are likely to find themselves stretched, to their ultimate benefit. Co-designing research lessons, for example, and examining their impact close-up, provides a set of lenses not available when one operates “at a distance.”

3. Pay attention to how the work fits into the larger system so that it has a greater chance of making a difference and of being sustainable over time.

It may be tempting to assume that those working in the school system will worry about how the partnership work will be absorbed by the system, but it can be very challenging for those who work day to day in schools or district offices to see the pond in which they are swimming. This has implications for partnership teams; it’s helpful to have diverse expertise because those best equipped to understand STEM

content are not likely to be the best equipped to understand school systems.

4. Work to build capacity.

4. Work to build capacity.

If the partnership is successful, it is because the researchers bring knowledge and perspective that was not inherent in the school system. Teams should engage in knowledge sharing, so that the system has greater capacity to continue the work after the formal conclusion of the project.

CADRE: What strategies have you found to be effective in addressing some of the typical challenges with enacting systems level reform?

1. Staff the partnership, not just the research.

Research practice partnerships are often considered to have two parties—the researchers and the practitioners. But neither researchers nor practitioners have expertise in the other’s line of work, and the incentives in their jobs are such that they do not fail if the partnership fails; Either can point to the other (often justifiably) as the problem. Project staff responsible for the partnership and accountable to both research and practice can keep things from falling between the cracks when pressures mount on practitioners or researchers to attend to their main foci...

Featured Projects

MIST (Middle-School Mathematics and the Institutional Context of Teaching)

MIST (Middle-School Mathematics and the Institutional Context of Teaching)

PI: Paul Cobb | Co-PIs: Kara Jackson, Thomas Smith, Ken Frank, Ilana Horn

Grade Band: Elementary

Reform: We addressed the question of what it takes to support teachers’ development of ambitious and equitable instructional practices on a large scale. Prior research demonstrates that teachers’ development of such practices is crucial if students are to attain rigorous learning goals that emphasize both conceptual understanding and procedural fluency.

Context & Audience: We partnered with large urban districts and worked closely with district leaders across multiple central office departments including Leadership and Curriculum & Instruction.

Approach: We established multi-year collaborative partnerships with four large urban districts. Our pragmatic goal was to add value to the districts’ instructional improvement efforts. Each year, we collected and analyzed data to document how each district’s current improvement strategies were playing out in schools and classrooms and to what effect, shared our findings with district leaders, and made actionable recommendations for how they might revise their strategies to make them more effective. Although our role was purely advisory, leaders acted on 67% of our recommendations. As part of this work, we delineated a view of high-quality mathematics instruction that is both equitable and aims at rigorous learning goals. We then mapped out from the classroom to investigate the implications for teachers’ learning, and thus for coaches’, school leaders’, and district leaders’ practices.

Our research goal was to identify a coherent set of instructional improvement strategies that would be relevant to other districts aiming at rigorous learning goals for all students. The longitudinal data set that we compiled spans from classroom instruction to district instructional leadership. In analyzing these data, we did not merely ask whether a particular improvement strategy was potentially productive but also investigated when and under what conditions it could advance the instructional improvement effort. As a consequence, our findings provide specific empirically-grounded guidance for school and district instructional improvement efforts. Although we focused on middle-grades mathematics, our findings are relevant to mathematics instruction at other grade levels, and to instructional improvement efforts in other content areas.

Key Challenge: We found that district leaders in the central office departments of Leadership and of Curriculum & Instruction typically pursue conflicting strategies for advancing student learning, and that these conflicts impede efforts that aim to support students in attaining rigorous learning goals. We found that senior district leaders could support leaders in these two departments in “getting on the same page” by clarifying that supporting all students’ attainment of rigorous learning goals was non-negotiable and by spelling out the implications for classroom instruction. In addition, it was important that senior district leaders make structural changes and organize work routines so that leaders in two departments collaborate routinely to design, implement, and revise instructional improvement strategies.

Theoretical Framework: In the course of the project, we developed what we call a learning design framework for assessing our partner districts’ improvement strategies. In doing so, we questioned the assumption that the failure of an instructional improvement strategy is the result of either willful distortion or resistance. This assumption overlooks the fact that instructional improvement strategies call for implementers to develop new capabilities and thus involves learning. This observation in turn implies that improvement strategies should include the provision of supports for that learning. We built on this insight by distinguishing between what we call the what and the how of a strategy. The what of a strategy corresponds to the envisioned types of practice that the strategy is intended to support. The how of a strategy refers to both the supports included in the strategy and the rationale for why these supports might be effective. The key question both when assessing a strategy before it is implemented and when accounting for how it is being implemented is whether the supports are adequate given the nature of the learning that the strategy calls for. To make this question tractable, we distinguished between four types of supports that capture all the improvement strategies that our four partner districts attempted to implement during our partnerships with them:

- The creation of new positions whose responsibilities include supporting others’ learning by providing expert guidance (e.g., coaches whose responsibilities included supporting and principals as instructional leaders).

- Scheduled meetings or interactions that constitute learning events because they can give rise to opportunities for participants to improve their practices (e.g., a series of professional development sessions for teachers, coaches, or school leaders).

- New organizational routines in which a more expert colleague scaffolds others’ learning (e.g., a routine in which a coach observes classroom instruction with school leaders then confers with them to discuss their observations).

- New tools (e.g., new instructional materials, curriculum frameworks, classroom observation protocols) that are introduced in intentionally designed learning events.

We found that strategies with the potential to support consequential professional learning involved some combination of new positions to provide expert guidance, ongoing intentionally designed learning events, carefully designed organizational routines carried out with a more knowledgeable other, and the use of new tools whose effective use was supported. The use of this framework was critical in enabling us to make feasible recommendations to our partner districts about revising their instructional improvement strategies.

Methodology: Each year, we documented each district’s instructional improvement goals and strategies, collected data to document how these strategies were being implemented and to what effect, and made actionable recommendations to district leaders about how they might revise their strategies to make them more effective. We developed this approach by adapting the design research methodology, which is primarily used to investigate teaching and learning at the classroom level, to investigate individual, collective, and organizational learning at the school system level.

Products: Recommendations for Improving Instruction at Scale | Publications | Interview Protocols | Sample District Feedback Reports: District B, District C

A Research-Practice Partnership to Develop Math Professional Development Leaders and Build District Capacity

PI: Hilda Borko | Co-PI: Janet Carlson

Grade Band: Middle

Reform: This Research-Practice Partnership between a university research team and the STEM department of a large urban school district is applying design-based implementation research to build and study district capacity to conduct school-based mathematics professional development by adapting, implementing, analyzing and revising interrelated models of professional development and teacher leader preparation.

Context & Audience: We have been working with district administrators, coaches, PD providers, and approximately 30 middle school math teachers from nine schools who participate as Teacher Leaders.

Approach: The specific problem of practice we are addressing is building capacity within the district to conduct school-based professional development to support teachers’ implementation of their new task-based mathematics curriculum and Dimensions of Learning and Teaching. We used the Problem Solving Cycle (PSC) and Teacher Leadership Preparation (TLP) models as the starting place for addressing this persistent problem of practice.

The PSC consists of three interconnected workshops, organized around a rich mathematical task. During the sequence of workshops teachers solve the math task in small groups and prepare to teach it, and then use video clips from their lessons to analyze student reasoning and instructional practices in the context of video-based discussions (VBDs). The purpose of the VBDs is to help teachers notice student and teacher practices during mathematics lessons so that they can improve the quality of their mathematics teaching. The TLP prepares Teacher Leaders (TLs) to plan and lead PSC workshops with the math teachers in their schools. The central component is a series of Leader Support Meetings that provide ongoing, structured guidance for the TLs as they prepare to lead PSC workshops. In a typical Leader Support Meeting focused on VBD, the TLs discuss the purpose of the upcoming PSC workshop and how a VBD can support that purpose, and they plan and rehearse their VBDs.

The TLPs were initially designed and led by the university project team. The district mathematics team assumed increasing responsibility for these meetings each year and now designs and leads the TLP independently.

Products: Video | Poster | Teacher Development Group Keynote Address | Publication

The Responsive Math Teaching Project: Developing Instructional Leadership in a Network of Elementary Schools

The Responsive Math Teaching Project: Developing Instructional Leadership in a Network of Elementary Schools

PI: Caroline Ebby | Co-PI: Caroline Watts

Grade Band: Elementary

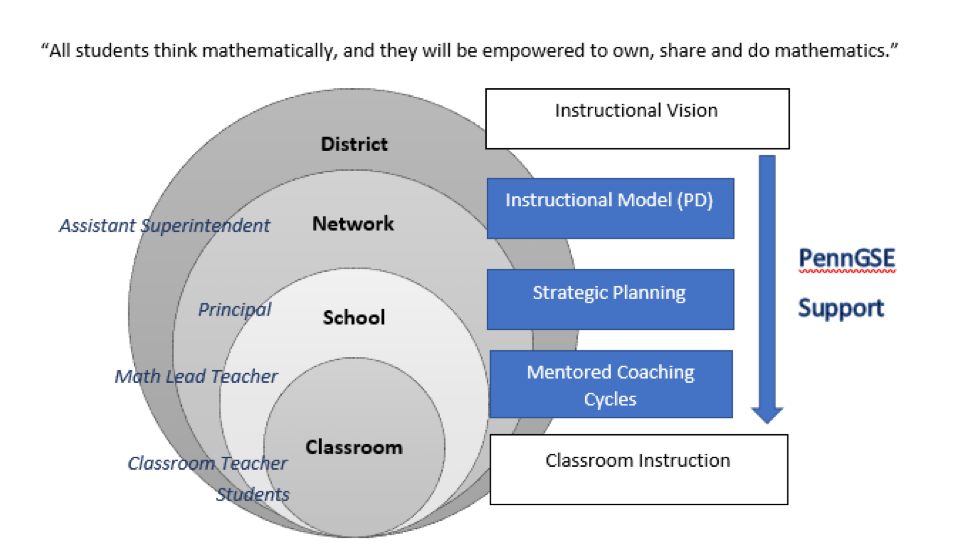

Reform: RMT is a research-practice partnership to build mathematics instructional leadership capacity in a network of urban elementary schools. Our aim is to build coherence throughout different organizational levels around the improvement of instructional practice by developing a set of tools and routines to help translate the district vision into classroom practice.

Context & Audience: The primary audience is districts, administrators, and teacher leaders seeking to improve math instruction and develop instructional leadership capacity at the school level.

Approach: This project is designed to build coherence throughout the different organizational levels of the instructional system (Cobb & Jackson, 2011) by leveraging the resources of the university to provide critical links to help translate district instructional vision into classroom practice. These linkages include developing shared understanding of the RMT instructional model at the network level, strategic planning at the school level, and mentorship to the math lead teacher to learn to provide instructional coaching at the classroom level. Each of these activities is designed to increase the depth of “routines of interaction” (Coburn & Russell, 2018) as classroom teachers engage with leaders around features of a shared understanding of mathematics instruction. Under this theory of action, mentors and coaches use the RMT instructional model to focus coaching and reflection on effective pedagogical practices and the quality of math instruction rather than on less impactful changes, such as the management of resources (e.g., providing new materials or pulling students out for remediation).

Approach: This project is designed to build coherence throughout the different organizational levels of the instructional system (Cobb & Jackson, 2011) by leveraging the resources of the university to provide critical links to help translate district instructional vision into classroom practice. These linkages include developing shared understanding of the RMT instructional model at the network level, strategic planning at the school level, and mentorship to the math lead teacher to learn to provide instructional coaching at the classroom level. Each of these activities is designed to increase the depth of “routines of interaction” (Coburn & Russell, 2018) as classroom teachers engage with leaders around features of a shared understanding of mathematics instruction. Under this theory of action, mentors and coaches use the RMT instructional model to focus coaching and reflection on effective pedagogical practices and the quality of math instruction rather than on less impactful changes, such as the management of resources (e.g., providing new materials or pulling students out for remediation).

University-based mentors support math lead teachers through professional development and side-by-side school-based coaching of selected classroom teachers. (The classroom teachers are also attending professional development around RMT). The mentor also engages school-based leadership in strategic planning to create a coherent plan for supporting math instruction and management of multiple initiatives and partners that may be working with the school.

Key Challenge: One of our key challenges is the issue of teacher turnover and retention. Like many large urban districts, the school district has a very high rate of teacher turnover or “churn” (teachers moving to new grade levels from year-to-year), particularly in lower performing schools. We realized early on in our project that it is important to develop instructional leadership capacity in a cadre of potential teacher leaders at each school. In addition to the designated math teacher leader, we try to identify and recruit additional grade level teachers that might serve as leaders for their peers at each school. We also hope that over time, offering teachers a pathway for professional growth within their schools may alleviate some of the turnover.

Products: Responsive Math Teaching (RMT) Instructional Model | Coming Soon! Project Website, RMT Lesson Planning Tool, and RMT Reflective Coaching Tool

Science Communities of Practice Partnership (SCOPP): Generating Reform Ownership for Transforming Science Teaching

Science Communities of Practice Partnership (SCOPP): Generating Reform Ownership for Transforming Science Teaching

PI: Kathryn Hayes | Co-PIs: Jeffery Seitz, Dawn O'Connor, Christine Bae

Grade Band: Elementary

Reform: SCOPP contends that effective and sustainable improvements in science teaching require teacher and administrator ownership and a supportive organizational environment. The project seeks to understand what reciprocal communities of practice (groups of teachers, leaders and administrators) add to the effects of typical professional development through a quasi-experimental study.

Context & Audience: This project studies implementation of an effective professional learning model for elementary science teachers that includes teacher leaders and administrators, taking a systems approach to improving science instruction across each district.

Approach: We are leveraging a currently successful university-district partnership to study pathways to sustainable instructional and organizational improvement. The following two principles form the basis of the models and tools we will be testing:

- Content and pedagogy PD alone are inadequate for effective and sustainable reform. Successful system-wide adoption of science standards requires ownership of reform among administrators and teachers alike, particularly at the elementary level (Bae et al., 2016a, Hayes et al., 2016).

- Organized, collaborative Reciprocal Communities of Practice (RCoPs) are critical for fostering ownership by building organizational and individual capacity. SCOPP focuses on three distinct RCoPs in which teachers, administrators, coaches, and faculty interact: District Leadership Collaboratives, Lesson Study, and Instructional Innovators (Bae et al., 2018; Hayes et al., under revision)

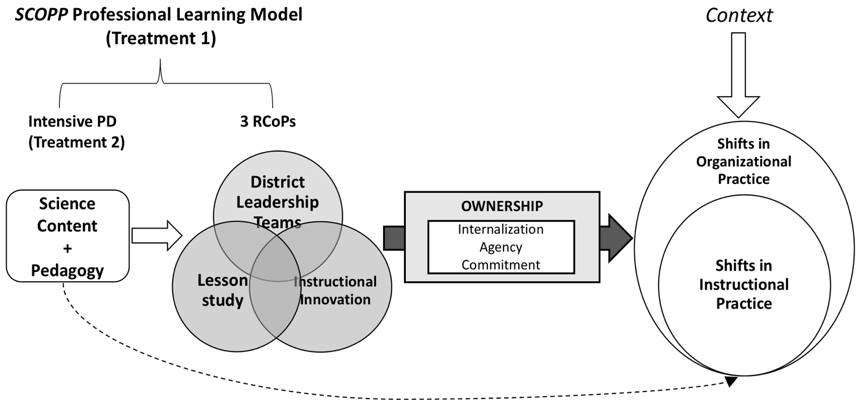

Based on these principles, the precise theory of change is as follows: ownership developed through ongoing participation in the RCoPs mediates the relationship between PD and long-term improvements in science instruction, and plays a critical role in why reform is scaled and sustained in some contexts and not others (Figure 1).

Figure 1: SCOPP Theory of Change Model

Although this theory of change is grounded in the literature and our previous work, it has yet to be tested at scale and across contexts. We have identified the following gaps for further study in SCOPP: First, the concept of ownership needs to be further operationalized and studied. Second, the mechanisms by which the three distinct forms of RCoPs function to support ownership (and in turn, instructional and organizational change) are in need of empirical study.

Key Challenge: Evidence suggests that exposure to science education in the elementary years is key to students’ later success in STEM disciplines. Yet exposure to quality science learning in elementary school is often haphazard and frequently nonexistent in high poverty contexts (Hayes & Trexler, 2016; Maltese & Tai, 2010). Reforming science instruction in diverse urban contexts is critical to addressing achievement gaps and accomplishing national goals for science education (NRC, 2013). Professional development (PD) is argued to be pivotal to supporting improvements in science teaching, yet current research on the role of PD in improving teacher practice is mixed (Adamson et al., 2013; Darling-Hammond et al., 2017). We argue that this is because current PD work rarely addresses the individual ownership and organizational conditions critical for fostering and sustaining improvements in instructional practice (NRC, 2015). The research is clear that simply increasing the skills and knowledge of teachers alone has little impact on systemic reform (Fullan, 2011). There is a need to develop effective individual and organizational professional learning models that translate content and pedagogy that are learned in PD into sustainable improvements in science teaching.

Theoretical Framework: To understand the factors that shape teacher instructional change, we draw on a previously developed framework characterizing the processes by which teachers change their instructional practice (Hayes, et al., 2019). As a foundation, the framework takes up Clarke & Hollingsworth’s (2002) propositions that teacher learning and change is an iterative process between new information, professional experimentation, observing student outcomes, and existing knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes. As teachers go through the process of instructional change, they also reflect on and are influenced by the requirements of their institution and other contextual factors (Allen & Penuel, 2015; Coburn, 2004). In order to understand this important influence on instructional change, our framework uses the concept of sensemaking from organizational theory (Weick, 1995). According to a sensemaking frame, when faculty encounter new pedagogical approaches, they will search for additional meaning from colleagues and the local environment in order to construct their understanding and shape action.

Methodology: The guiding research question is What is the role of the SCOPP Professional Learning Model in developing science reform ownership and shifting organizational conditions, and how do ownership and supportive organizational conditions subsequently facilitate improvements in elementary science teaching?

Setting

This project will include two districts per condition (Treatment 1 vs. Treatment 2 vs. comparison). The district partners represent high poverty, diverse urban contexts, and each district selected six schools to participate. The program focuses on grades 3 to 5, recruiting one teacher from each grade level per school (in the treatment districts) to cultivate as lead science teachers for their grade.

Research Designs

- Mixed-Methods Convergent Design. We propose a convergent parallel mixed-methods design (Cresswell & Clark, 2011) to both quantitatively test the relationships between the constructs under study, and qualitatively develop theory regarding the conditions that support improvement in science teaching. As described below, we will independently analyze quantitative and qualitative data. Results will be mixed during interpretation to develop inferential and explanatory accounts of the relationships among SCOPP professional learning, ownership and organizational conditions, and improvements in science teaching.

- Longitudinal Quasi-Experimental Design. For the quantitative evaluation of SCOPP, the longitudinal quasi-experimental design will follow three conditions: two treatment groups and a comparison group over 3 years. This design will allow us to test the effects of the SCOPP learning model on our outcomes of interest over time. While the primary contrast of interest is between Treatment 1 (full SCOPP model) and Treatment 2 (Intensive PD only), we will compare the two treatment conditions against a comparison group composed of non-participating teachers in the treatment districts. This comparison will test whether or not treatment effects spread within schools.

- Qualitative Explanatory Design. We use an explanatory design in order to understand the sequential and iterative processes by which teachers improve their practices in the context of SCOPP. Data for qualitative analysis (interviews, audio recordings of RCoP meetings, classroom videos) will be collected from a nested, purposive sub-sample (Creswell & Clark, 2011). Analysis of interviews and recordings will focus on developing the theoretical conceptualization of ownership, as well as the processes by which RCoPs influence instructional and organizational practices. Interviews will also provide a description of how and why teachers modify their practices in relation to ownership. Classroom videos will capture whether and in what ways the targeted instructional shifts develop over time. Iterative testing of tools. SCOPP plans to include a series of rapid design cycles (Bryk et al., 2015) that will test, refine, and validate four tools prototyped in a prior NSF project by (1) gathering evidence of effectiveness, (2) focusing on variation in use of tools across contexts (e.g., user-based implementation), (3) refining tools based on feedback, and (4) disseminating tools.

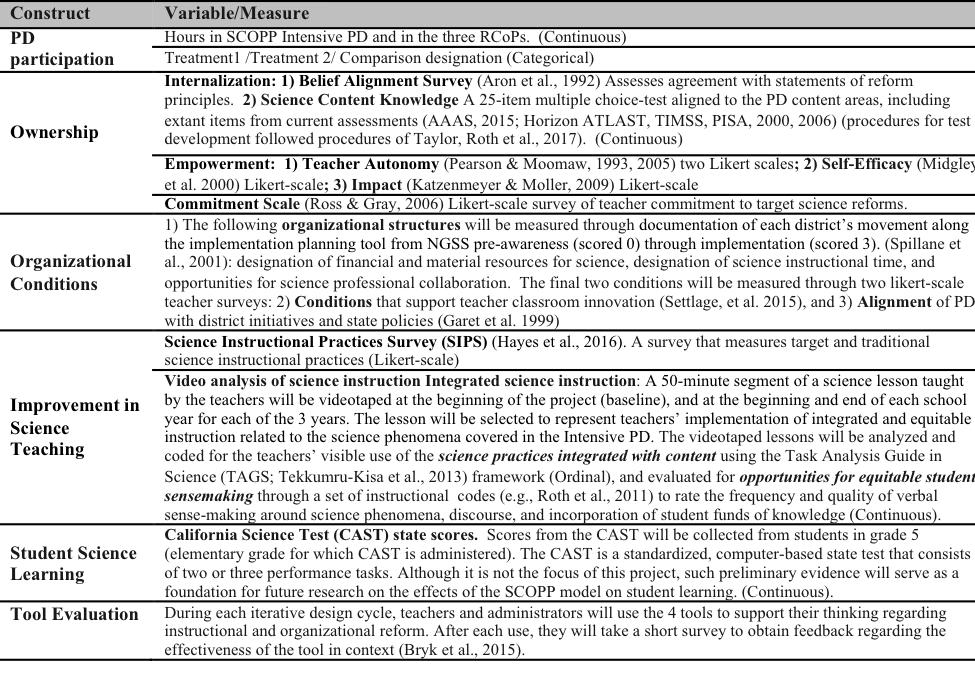

Measures

Table 1. Description of constructs and quantitative measures.

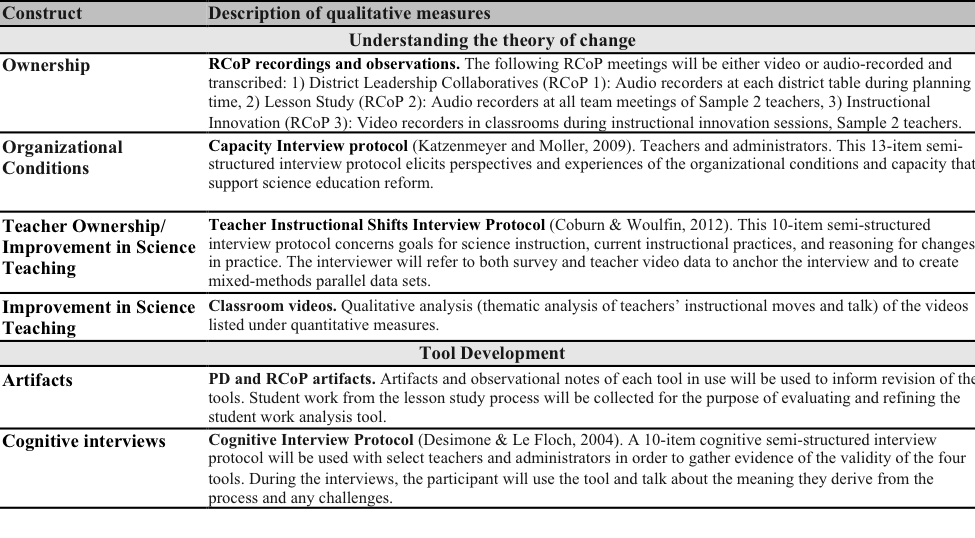

Table 2. Description of constructs and qualitative measures.

Products: Guide to District Action for NGSS | Science Instructional Practice Survey | Teacher Leadership Typology | Online Science Content for Teachers | Publications

Testing a Leadership Development Model for High School Science Reform and the Relationship of Key Variables to Student Achievement

Testing a Leadership Development Model for High School Science Reform and the Relationship of Key Variables to Student Achievement

PI: Jody Bintz | Co-PIs: Joseph Taylor, Molly Stuhlsatz

Grade Band: High

Reform: The mission of the BSCS National Academy for Curriculum Leadership (NACL) is to assist schools and/or districts in building the capacity to design, implement, and sustain an effective secondary science education program using high-quality instructional materials as a lever for change.

Context & Audience: The NACL is an intensive three-year program for district-based secondary science leadership teams that include a key administrator, team coach, and teacher leaders.

Approach: The NACL program consists of three annual face-to-face meetings plus local technical assistance. The program emphasizes four intended district-level outcomes with a strong theoretical base and empirical evidence of their potential to improve student learning. The strategies and intended outcomes are the:

- implementation of research-based instructional materials supported by high-quality professional learning;

- development of effective professional learning communities that focus specifically on the implementation of research-based instructional materials;

- garnering of organizational support to ensure sustained curriculum reform efforts; and

- development of leadership capacity.

The NACL was developed and tested in the early 2000s with support from the National Science Foundation (NSF DRL-9911615) and taken to scale in the state of Washington from 2004-2010 in collaboration with Washington State LASER, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Pacific Science Center, and with major funding from Battelle and Agilent Technologies Foundation.

The retrospective study of the NACL was funded by the National Science Foundation (DRL- 1316202). This longitudinal study investigated the effects of the NACL by propensity score matching a comparison group of similar districts who did not participate in the NACL. Longitudinal treatment effects suggest that outcomes were similar for students in treatment and comparison districts in the beginning of implementation, then a dip occurred for treatment districts, with a rebound occurring in treatment group outcomes by year seven. Analyses of data from treatment districts suggest a strong positive association between higher student outcomes and both the existence of highly functioning professional learning communities and higher retention of leadership team members over time.

Products: Publication (In Press)

A Three-Way Partnership to Build School District Leadership in Scientific Argumentation

PIs: Hilda Borko, Emily Weiss | Co-PIs: Jonathan Osborne, Craig Strang

Grade Band(s): Elementary

Reform: Our Research-Practice Partnership between Lawrence Hall of Science, Stanford University and a local school district is designing and researching a sustainable program to prepare teacher leaders to facilitate teacher professional learning. Ultimately, our goal is for students in grades 2-5 to argue from evidence when they are learning science.

Context & Audience: Our activities target school district administrators, teacher leaders, and teachers. The project’s products will also inform the work of professional learning leaders and education researchers.

Approach: Our Research-Practice Partnership uses a Design-Based Implementation Research approach design, implement, and study a program to prepare professional learning leaders. It involves three partner institutions:

-

professional learning and evaluation teams from the Lawrence Hall of Science (the Hall), University of California, Berkeley,

-

a research team from Stanford University,

-

and a team of teachers and administrators from Santa Clara Unified School District (SCUSD).

Key Challenge: A challenge to implementing reforms through a research-practice three-way partnership is to work efficiently while taking partners’ input into account, in particular the district’s. We are regularly asking ourselves questions such as whose voice should be at the table, when should it be there, and what are the pieces that each voice should have influence over?

We are working on structures to address these questions. These structures are being developed with the input of all three partners: the district, the professional learning team, and the research and evaluation team.

Here are some strategies we have used/are using that are helping the process along. Each strategy opens spaces for input from different roles within the district (teachers, teacher leaders, or administrators), as well as from other teams.

-

District administrators’ endgame planning needs: The project PIs meet quarterly to plan how to meet the district needs/goals through sustainable changes. This is allowing them to be present- and future-focused simultaneously. The district assistant superintendent, elementary curriculum and instruction lead, and science teacher on special assignment are all present for these meetings with the other project principal investigators.

-

District administrators' day-to-day needs: A researcher is meeting almost every week with the district's science teacher on special assignment. She is keeping them updated about what's happening in the District, and they discuss about whether the partnership is supporting their needs. These 30-minute to 1-hour interviews allow us to identify issues that the project's leadership team needs to address in their bimonthly meetings. These bimonthly meetings include at least one district administrator.

-

Project leadership team needs: A leadership team meets bi-monthly.These meetings are not usually focused only on the district, but on other partners' needs as well. The members include the Stanford and Hall PIs, at least one member of the district leadership team (more when they are available), our evaluation team lead, and the postdoc coordinating the project’s day-to-day activities.

-

Teachers' professional learning and students' needs: Throughout the year, the professional learning team from the Hall organizes 4-6 follow up days to facilitate activities that support teachers in implementing argumentation. Among other activities, they use a protocol to reflect on teachers' and students' practices using classroom videos of themselves. During the follow up days, the research team is observing if the professional learning team is meeting their goals and makes notes of observations that would be interesting to share with the professional learning team. The science teacher on special assignment is participating in the professional learning in the role of a teacher leader and makes observations about whether/how the activities support the teachers' needs. At the end of each follow up day, the Evaluation team surveys the teachers to identify which areas they still need support in. After each follow up day, the science teacher on special assignment, members of the research and evaluation teams, and the professional learning team meet to debrief each day to determine areas to tackle with the teachers in the next follow up day, and to design activities to achieve that.

Products: Video (2019) | Video (2020)

TRUmath and Lesson Study: Supporting Fundamental and Sustainable Improvement in High School Mathematics Teaching

TRUmath and Lesson Study: Supporting Fundamental and Sustainable Improvement in High School Mathematics Teaching

PIs: M. Suzanne Donovan, Alan Schoenfeld | Co-PIs: Phil Tucher, Catherine Lewis

Grade Band(s): High

Reform: TRU-Lesson Study integrates the Teaching for Robust Understanding (TRU) framework and Lesson Study into a strategy for teacher professional learning. TRU focuses attention on classroom features that produce powerful, resourceful mathematical thinkers and problem solvers. Lesson Study supports ongoing cycles of instructional improvement in which teachers enact and study TRU.

Context & Audience: The project targets teachers and teacher-leaders/coaches intensively. District and site administrators are also targeted as essential supporters and protectors of teachers’ time and focus.

Approach: TRU-Lesson Study integrates the Teaching for Robust Understanding (TRU) framework (the theory of what matters) and Lesson Study (a strategy for changing practice). The work is site-based, engaging teacher learning communities (TLCs) in ongoing exploration of mathematics, student learning, and key dimensions of student-focused learning environments. Research indicates that students emerge from classrooms as knowledgeable and empowered thinkers when (1) the content is rich, (2) students work at the right level of “productive struggle,” (3) all students have access to core content and (4) opportunities to develop a sense of disciplinary agency and positive disciplinary identities, (5) optimized through formative assessment. These are the five dimensions of the TRU framework.

In Lesson Study, teachers collaboratively study content, and plan, teach, and refine “research lessons” that are taught by one team member while others observe and record student responses. TLC members share and discuss the collected data to understand how their pedagogical hypotheses fared in practice, and to identify next steps in improving instruction. Research indicates that Lesson Study can build teachers’ content knowledge, collegial effectiveness, and attention to student thinking.

A key to successful implementation is balancing district and site coherence with teacher autonomy. TLCs need district and building leaders’ support so their time is protected, and their work is not undermined by competing initiatives or district requirements. Once within that TLC, however, teachers must have significant latitude in choosing which problems to address in order to have the agency and ownership that will drive changes in practice.

Key Challenge: Many urban districts are under-resourced and under scrutiny. Publicly visible priorities—a teacher in every classroom, a principal in every school to manage crises, buses running on time—demand attention. Less visible investments in time for teacher learning and in high-capacity coaching to support that learning are often squeezed to meet budget constraints. Thus, there is too little attention to, and capacity for, coherent, sustained learning opportunities for teachers that focus on what counts.

Our strategy has been: a) to situate the partnership at the district level and engage the central office leader for mathematics as a project co-PI; b) to work on a problem the district math team considers a high priority; c) to host an event where both the participating principals and their supervisor (Assistant Superintendent) were present so that the message of support from the top was clear, and so that principals saw themselves as part of a larger initiative; d) to support the district by providing funding for specialists during the project who provided capacity to teacher teams, and who built the internal capacity of those teams to continue the work; and e) to interview the principals periodically throughout the project in order to be responsive to their concerns and needs and to maintain their awareness and support for the project. The effectiveness of these strategies varied across schools, with turnover in personnel at the district and school level, and multiple competing initiatives vying for teacher time playing a significant role in variation across sites.

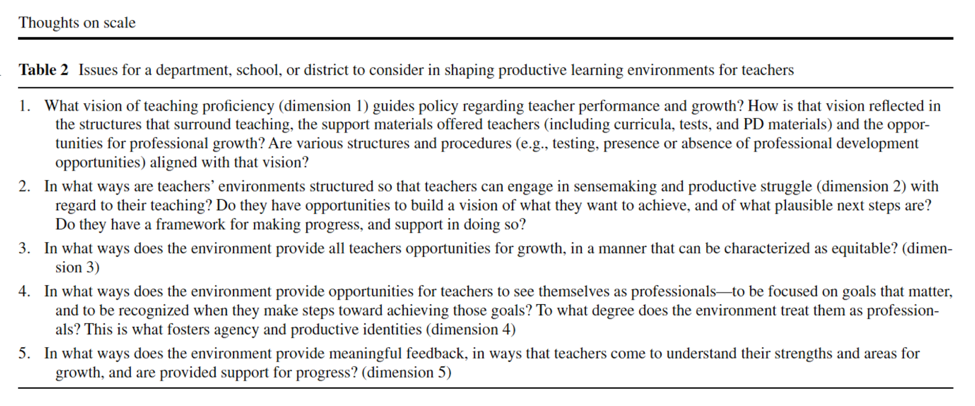

Theoretical Framework: Our theoretical framework considers systemic reform as a learning agenda. It places a vision of high-quality teaching and learning environments at the center (the TRU framework) and is driven by coherent efforts to understand (at varying levels of detail) and support that vision at all levels of the system. (Cobb, Jackson, Henrick, Smith, & MIST, 2018; Forman, Stosich, & Bocala, 2017).

The table below provides a description of the TRU framework when applied to teachers’ learning environments.

Methodology: Our intervention targeted teacher learning. Our approach to understanding its effects includes:

- Intensive video analyses of teacher team meetings

- Observations in teachers’ classrooms over time

- Survey of teachers’ beliefs

- Evidence of teachers’ ability to “see” instruction (video-based) differently over time

- Measures of student learning (limited by district assessment strategies and data collection opportunities)

Products: District Partnership Website | Publications | TRU Framework & Tools | Lesson Study Information & Resources